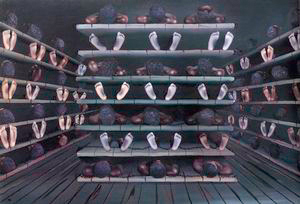

During the late 16th century to early 19th century the Transatlantic Slave Trade was operated in order to transport various things. These things included crash crops, goods, clothing, food, and slaves. This is a drawing depicting the captives on the French slave ship, Vigilante. The image illustrates how captured slaves were transported to The New World. The diagram shown in the image shows the ship itself, the shape of the ship, and the containers it held inside. On the side, there are also different diagrams of the chains used to hold down the captives. This image depicts how the slaves were transported one on top of the other as cargo, the captives were stacked and made to sit in order to fit as many as possible. As one sees it you become aware of the inhuman ways in which slaves were transported and how they had to deal with being cramped up in a place for days on end. As one sees the image it gives the observer the feeling of melancholy at the atrocity these victims had to suffer for the profit of others. Based on these images I would like to read a little more about the overall shipment of slaves I think that it is something that shows the dehumanization of the slaves in that they were shipped like livestock. Some of the questions that this image might raise are how were such treatment of human beings allowed and encouraged? What thoughts did these victims have after having being treated in this manner?

In her poem “On being brought from Africa to America” Phillis Wheatley speaks about her experience in having been taken to Africa and brought to America, in her poem she gives details and thanks God for her voyage. The poem begins with the narrator telling the readers about the “mercy” of being brought from Africa, which is described as a “pagan land” (1). Then she states that this mercy has taught her “that there’s a God, and there’s a Saviour too” (3). She ends her poem by telling her readers “Remember, Christians, Negroes, black as Cain,/ May be refin’d, and join th’ angelic train” (7-8) telling people like her that even with all their “sins” and “darkness” they can still find salvation. With her words she shows how people saw people of color, she then tries to persuade them of the blessing that it is to be taken from Africa. She gives her readers a sense of hope that just as she has experienced religious salvation so can others as well if they just repent. We should take into consideration that these poems were written by a slave woman for a predominantly white audience. Her poems and her works had been published with the help of her owner, the reason for the success of her poetry was because as shown in this poem she does not speak out against slavery. Instead, Wheatley supports slavery or gives another benefit by showing people that slavery liberated her from the pagan religion she had once served. With this ideal, many people also came to believe that slavery also saved people from sin and paganism by converting them to Christianity.

The image shows a different view in the voyage to America from Africa in the poem written by Phillis Wheatley “On being brought from Africa to America.” This image illuminates the different views of the voyage to America, some held the ideas that it was a salvation from the “savagery” of Africa and its culture. This image goes against the ideas that Phillis Wheatley had about her voyage to America, she perceived it as a salvation and a gift from God. The terrible conditions in the image show that it was far from a blessing for those that endured it. The image shows us with great detail the way in which slaves were brought from Africa. As we see in the image some of them were laid out side by side and in the middle of the boat, many others were sat down in neat rows. Although one might think this would be uncomfortable at worst, we must remember that they had to stay in those positions for months at a time. In addition, during this voyage, the captured people did not see the light, did not have water or food and had to defecate and relieve themselves right in the same area. The heat of the place must have also been unbearable after many days in the same area, and the smells of bodies and feces must have been even worst with this heat. Unfortunately, it did not end there many perished during that trip and their decomposing bodies were left there for days. That is just some of the things they had to endure, not to mention rape, murder, and other such atrocities.

Moreover, For Wheatley, her experience in slavery was described by her as a positive miracle, something that saved her from the backwardness of her society and culture. In her poem Wheatley never speaks out against the system of slavery, instead, she appreciates it because it has brought her what she deems salvation from the savage ways. Her poem speaks about the miracle of having been brought to America, the image shows that the trip itself showed the lack of empathy from that captured them. Wheatley does not describe for us how she was transported from her home, instead, it informs us of the blessing that it has been in her life to travel to America where she was able to learn Christianity. The diagram shows us that this voyage was a far cry from a vacation or a miracle, it was a imprisonment and a death sentence.

Although Wheatley did not have the same life as many other slaves or the same ideas about slavery, she still experienced it and the long voyage to America. This image shows the conditions in which Wheatley most likely traveled, giving evidence that the voyage and destination were far from a blessing. It also gives a voice to all of those slaves that died in transit to new places due to the conditions portrayed in the image, those who see it will be able to understand just one part of the Triangular Slave Trade. From these two sources, we can see two widely different points of view on slavery. Both of these sources are very informative for us and give us two opinions that show us that the variety of human thinking is. In the end, it gives us a tiny glimpse into slavery and the things that slaves endured.

Work Cited:

- Wheatley, Phillis. “On Being Brought from Africa to America.” Complete Writings, edited by Vincent Carretta, Penguin, 2001.

- Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library. “Interior of Slave ship, Vigilante.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47dc-4d67-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99