The lithograph called Plantation Cooks, Suriname, ca. 1831 from the The University of Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, and the fictional events in Oroonoko: or the Royal Slave. A True Story by Aphra Behn were both inspired by voyages to Surinam, a colony belonging to the King of England, currently called Suriname and situated next to Ghana. The two conceptions reflect the slaves’ lives in a shared location in different centuries and perspectives. The contents in the illustration contradict the perception of life as a slave from Behn’s narrative of Oroonoko’s experience.

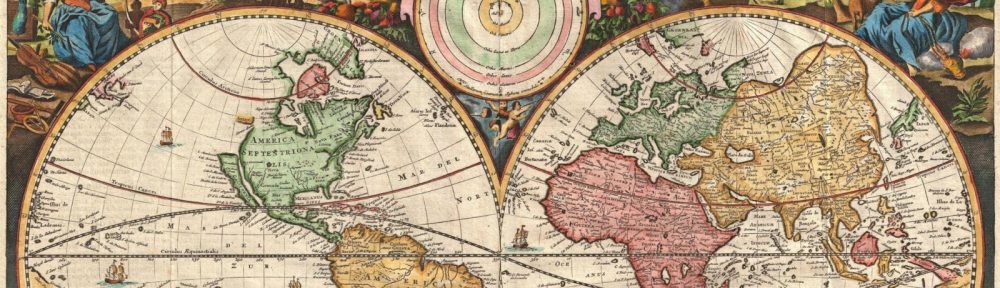

The illustration, Plantation Cooks, presents a moment in the tough daily routines of the kitchen slaves in a plantation in Surinam. The layout includes an open porch in the masters’ house counting four adult slaves, two in the center and two to the sides, a teenager and two infant slaves as well as some animals and elements of nature. Overall, the image emphasizes the working adults while keeping the young ones in the shadows, as if the artist intended to hide the sad reality of their fate as born slaves; or, as if he felt guilty and wanted to protect the children’s illusion by keeping the cruel truth buried in the dark.

In Aphra Behn’s narration, Oroonoko’s responsibilities as a slave or mistreatment from his two masters are nearly nonexistent during most of his slavery lifetime. The protagonist, an African prince in his nation, has the unfortunate fate of becoming a slave in a plantation in Surinam. There he reunites with Imoinda, the love of his life whom he thought dead, and starts a new life with her. After her pregnancy, he fights to obtain his family’s freedom but ends up killing his wife and unborn child and is ultimately mutilated by the deputy governor. Oroonoko was published in 1688 whereas Plantation Cooks, in 1831. In Oroonoko’s timeline, the slave trade was less developed, but the discrimination against slaves was largely just as cruel.

Oroonoko receives special treatment ever since his first day at the plantation. The narrator said, “But as it was more for form than any design to put him to the task, he endured no more of the slave but the name, and remained some days in the house, receiving all visits that were made him, without stirring towards that part of the plantation where the Negroes were.” (44) The statement confirms Oroonoko’s slave status as a façade and the purpose of his new name as for appearances only. Thus, he never had to worry about any of the responsibilities belonging to a true slave. Contrasting Oroonoko, the adults in the picture perform their household tasks while the children expect their little share of food. The man on the left is using a mortar and pestle and the woman on the right is sitting next to the fire cooking the fish in the net above. Inside the porch, covered by the shadows, a boy is sitting eating fish; his short hair and reedy arms suggest he is a teenager. Towards the back of the porch, a woman is walking away while carrying a weight on her head and arms, presumably food. The two infants are sitting on the floor; the oldest holding a bowl and the youngest grabbing the eldest’s arm while staring at the bowl, possibly asking to be fed.

As the passage indicates, the only servitude quality the masters impose on Oroonoko is his name, Caesar (43). This name remembrances the Roman leader Augustus Caesar, which correlates to the newly-introduced European customs rather than to his African origins. The statement also has a condescending tone towards the “Negroes.” According to the OED, the term was given to members of a dark-skinned group of peoples originally native to sub-Saharan Africa; of black African origin or descent. Formerly frequently with the implication of being a slave. There is a clear distinction between Caesar and the rest of the slaves regarding consideration. Besides his dark color and African origins, the slave is treated as a guest in the plantation and welcomed by distinguished families who visit him frequently. Eventually, Caesar earns the designation of “royal slave,” since he acts and is treated like a prince.

The most significant differences between the lives of the plantation cooks and the royal slave are the responsibilities in the master’s house and the treatment from the white masters. In the illustration, the masters are absent, but the unhappy expressions in the faces of the slaves evoke their fatigue from carrying out their tasks and their sadness from being tied to it for life. However, the masters in the novel immediately place Oroonoko in a higher standard than the regular plantation slaves and give him all the comforts they can with the limitation of his freedom. Surinam’s slaves in Oroonoko’s timeline are similar to the slaves in the archive. They work hard at the plantation. They are looked down upon by their masters and have no longer the freedom to do whatever they wanted. It is unreasonable that Oroonoko, alias Caesar, receives so much attention and admiration from the two white masters and even from the author while maintaining the same slave status as the plantation cooks.

As a reader, one may wonder if the narrator had too much admiration towards the slave and failed to relate his life correctly; or, what Behn’s viewpoint in slavery was. As a viewer, one may wonder if the two central adults in the illustration and the children are related, and whether they ever thought about risking their lives to escape slavery. One may also be curious about the female slave’s thoughts at that moment. Her conscience seems lost, looking for an answer to her internal questions in those flames. Some may think Oroonoko’s fate may have been different if he had behaved like a real slave. He may have recognized his role as a working slave and given up his and his family’s freedom in exchange for long life in the plantation.

Works Cited:

- Behn, Aphra. Oroonoko, edited by Janet Todd, Penguin, 2004.

- Pierre Jacques. Plantation Cooks, Suriname, ca. 1831. Slavery Images: Voyage a Surinam. The Atlantic Slave Trade and Slave Life in the Americas. The University of Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, Virginia. http://slaveryimages.org/detailsKeyword.php?keyword=surinam&recordCount=61&theRecord=3

Excellent analysis of your essay on “Ooronoko’ and the “Plantation Cooks” painting. I’m not exactly sure that he is treated royally as slave.But I do notice that he has been given special treatment compared to the other slaves. As for the “Plantation Cooks”, they are what considered as house slaves, whose work revolves around the master’s house. Compared to the field slaves their work is less labor intensive and are treated slightly more respect by their master’s. Overall this essay really experiments the

field slave vs. house slave aspect.