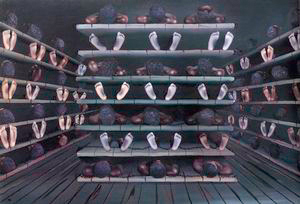

Within the confines of the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture: “In Motion: The African American Migration Experience”, there exists an image of particular profundity. It is not a spectacular work of art, but it is emotionally strenuous for the viewer to look upon. This oil painting by Rod Brown is titled “Sheol” and was published in 1998. It is included in Julius Lester’s From Slave Ship to Freedom Road. An apposite piece is the literary work Oroonoko by Aphra Behn. Published in 1688, Behn wrote using various themes that could be aligned with the abolitionist movement. Some might argue that Behn’s novella detailing the royal slave and violence he instigates and endures could be read as meant to encourage sympathy and tolerance in an era marked by the abasing of Africans. This ambition is shared by both Brown and Behn. And though their respective goals regarding the portrayal of the slave trade as a means to encourage sympathy are comparable, they differ in their executions, severity of images used, historical accuracy, relatability and the emotional ramifications presented to their audiences.

An observer will notice that the oil painting shows a group of newly captured slaves held in place by chains. They remain in the hold of the ship. The men and women shown are tightly packed and seem to have no measure of comfort. Solace is impossible when brutally bound by the feet and neck in total darkness. Only the bound parts of the slaves are visible to the viewer. In its entirety, the image of enslaved people is akin to looking upon crates of invaluable commodity thrown together without regard for empathy. This impression is masterfully created by Brown. He expresses the suffering narrative by painting groups of twenty-one humans staked into a space for less than three through the use of restrictive wooden boards. Brown’s color palette is as dark and dreary as the implications for how these slaves were managed.

Oroonoko, is the tale of an innocent, valorous and benevolent African prince who is forced by circumstance to become the rugged leader of a rebellion from bondage. Throughout the novel, Oroonoko is motivated by his love for Imoinda to attempt to shape his uncertain future. Each of these endeavors fail tragically. At the upshot, the protagonist is gruesomely tortured and killed but only after he murders a pregnant Imoinda. However, Imoinda was not the victim of her husband’s rage. As Oroonoko draws his knife to kill his wife, Imoinda was “smiling with joy she should die by so noble a hand” (Behn 61). Euthanasia was the only manner in which Oroonoko could spare his beloved wife and unborn child from the horridness of severe subjugation. Behn proclaims that “this cruel sentence” of slavery is “worse than death” (Behn 24). Conversely, a notion such as a preference for an immediate demise over servitude is incongruent with Behn’s portrayal of slavery up to this point.

Clearly, the mentioned oil painting and abolitionist novel are connected in their narrative regarding the suffering of enslaved people. However, when the two works are juxtaposed a new perspective is created. “Sheol” attempts to show the dark reality of the slave trade while Oroonoko shields the reader from its true barbarity until the novel’s upshot. For instance, an inebriated Oroonoko is brought aboard the ship by treachery and not violent force. In response, the venerated principal character refuses sustenance in the hope that he will perish and escape such indignities. His fellows follow suit until the Captain releases Oroonoko from the chains which bound him. Once the chains were removed from Oroonoko “they no longer refused to eat… and were pleased with their captivity, since by it they hoped to redeem the prince, who, all the rest of the voyage, was treated with all the respect due to his birth…” (Behn 33). This scene is described in a sanitized manner that seems less than parallel to the event portrayed in the painting. Unbelievably, the thralls transported alongside our protagonist are referred to as being content with their bondage.

It is peculiar that that Aphra Behn would utilize the happy slave trope. The contentment of the bondman is not maintained throughout the entirety of the novel, but regardless it is damaging to the cause. Perhaps the author of Oroonoko simply wished to preserve the relative innocence of her protagonist. At the point in which Behn’s fictional paladin was to be auctioned off “he nimbly leaped into the boat and, showing no more concern, suffered himself to be rowed up the river” (Behn 34). By maintaining Oroonoko as a man not yet tainted by true atrocities he would battle later in the story, the character development leading him to murder his wife is far more dramatic. In contrast to this, “Sheol” paints a more barbarous image for the psyche. It exhibits a single moment fixed in despair but is enough to imagine the entirety of the journey through context. On the other hand, the text is incomplete for it only displays a single, extraordinary individual. The object manages to enrich the text by expanding upon the scope to show the experience of the ordinary slaves shipped through the Middle Passage. Behn’s fiction regarding the Royal Slave is incongruent with the stories left behind by the survivors of the Middle Passage. For that reason, each detail presented by Behn must be evaluated in terms of a truly accurate depiction of these historical matters.

To build upon the aforementioned image, the oil painting is aptly accompanied by a caption from Mahommah Gardo Baquaqua’s Biography. Baquaqua describes the peril experienced by himself and those bound beside him on a forced journey to Brazil. Naked and deprived of sunlight, they could no longer tell the time of day until they “became desperate through suffering and fatigue” (Biography of Mahommah G. Baquaqua). This remark is a befitting emotional description of how men shelved in the insolation of darkness must have felt. Thusly, Bacquaqua’s rendering is far more analogous to the painting than Behn’s novel. Both Bacquagua and Brown presented ghastly images that could hopefully shock viewers into feeling sympathy.

Due to the great disparities in these two works, it is difficult to see any common ground they share regarding their respective portrayals of the slave. “Sheol” nearly contradicts the representation of the text. Shortly after being captured, Oroonoko manages to converse and reason with the ship’s captain. His “command was carried to the captain, who returned” (Behn 31) with a response in kind. While this is not a statement to equality, it shows the Africans and their captors as being close in terms of their social stations. Contrary to this, the Africans depicted in the oil painting have no means to complain or find resolutions to their perils. Instead, they can only suffer in silence. And even though the presence of the jailors is physically omitted from the art piece, the psychological repercussions can still be observed. The slaves are allowed no movement, for this would show liveliness. Alternatively, this still life painting creates a feeling of oppression that has thoroughly permeated the spirit of the captives.

It can be reasoned that the defeated manner in which the captives are shown in “Sheol” is intentional. Brown put great detail into the visible body parts of the enslaved people. These viewable portions are restricted to the crowns and the soles of the bound men. Including faces would humanize the men and women depicted. Referring to them as men and women should be done in the liberal sense, since no sexual characteristics or any other distinguishable characteristics are created. By these means Brown mimics the dehumanizing process which was used against these human chattels. Furthermore, the viewer is unable to look upon the faces of the captives and make judgments of their perceived emotional states. This contrasts profoundly with the fully fleshed out character of Oroonoko. Behn writes that he died a “great man; worthy of a better fate” (66). After all the indignities forced upon her title character, she elucidates her hope for “his glorious name to survive to all ages” (Behn 66). In essence, Aphra Behn, refused to bestialize or subvert her protagonist so that it would be more difficult for her audience to condone the dehumanizing of slaves during the period in which Oroonoko was written.

Rod Brown’s “Sheol” and Aphra Behn’s Oroonoko paint remarkably different tales of Africans being oppressed by the systematic capture, abuse and sale across the Middle Passage. One attempts to bowdlerize the experience of shackled men and women for the sake of preserving the narrative and the integrity of the character. Hence, a deeply involved and empathetic tale is created. Meanwhile, the other (“Sheol”) manages to build an equally sound argument against the slave trade by producing an image in which no characters are developed, but many are dehumanized accurately. These two artifacts raise questions regarding the reliability of any such representations. The incongruencies between the works of Brown and Behn show how art can be warped or focused by specific agendas as they are conveyed to viewers.

Works Cited Page

Behn, Aphra. Oroonoko, edited by Jim Miller, Dover Thrift Editions, 2017.

Brown, Rod. “Sheol.” From Slave Ship to Freedom Road, 1998, General Research and Reference Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. http://www.inmotionaame.org/gallery/detail.cfm?migration=1&topic=99&id=297611&type=image&metadata=show&page=6

Baquaqua, Mahommah Gardo, and Samuel Moore. Biography of Mahommah G. Baquaqua: a Native Zoogoo, in the Interior of Africa (a Convert to Christianity). CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform?, 2012.